Understanding FDA Literature Review Requirements

The FDA requires literature reviews to ensure that regulatory decisions are based on solid scientific evidence. This isn’t just about compiling papers; it’s about systematically searching, appraising, and synthesizing published data to demonstrate safety, efficacy, and compliance. These requirements span multiple domains, from drug approvals to medical devices and health claims.

For drug approvals, literature reviews are integral to pathways like the 505(b)(2) New Drug Application (NDA), which allows sponsors to rely on existing studies and literature rather than conducting full original trials. In Investigational New Drug (IND) applications and postmarketing surveillance, sponsors must monitor global literature for safety signals, reporting serious unexpected adverse events within 15 days. This includes reviewing published and unpublished reports on products with the same active moiety, even if formulations differ.

In medical device submissions, published literature can substitute or supplement clinical data, especially for Premarket Approvals (PMAs) or supplements for Class III devices. Under 21 CFR 860.7, evidence must provide “reasonable assurance” of safety and effectiveness, with literature needing to be sufficient, detailed, objective, and directly applicable. For instance, reports from U.S. or foreign marketing experiences can bolster applications if the underlying data is accessible.

When a company wants to claim that a food or supplement helps with a disease, the FDA reviews the scientific literature to see if the link is real, and it focuses on human studies. To be approved, the claim must be backed by “significant scientific agreement” (SSA) or, for qualified claims, at least credible evidence.

FDA Evaluation Process

The FDA requirements start with a structured approach. Here’s how it is typically carried out:

- Planning the Search: Define clear objectives, search terms, and inclusion/exclusion criteria. For FDA compliance, searches must be global, repeatable, and documented to capture all relevant safety and efficacy data. Avoid overly restrictive terms to prevent missing critical events.

- Conducting the Review: Prioritize high-quality human studies. Intervention studies (randomized, controlled trials) offer the strongest evidence for causality, while observational studies (e.g., cohorts) support associations but are prone to confounders. Evaluate for methodological quality: randomization, blinding, confounder adjustment, and validated endpoints.

- Appraisal and Synthesis: Assess the totality of evidence for consistency, replication, and relevance to the U.S. population. Flawed studies (e.g., lacking controls or with high attrition) are discarded. For devices, ensure access to protocols and raw data.

The Game-Changer: Where AI Fits into the FDA Workflow

AI is relevant and appropriate at various stages of the review process, turning that manual slog into a more manageable, intelligent workflow.

1. Supercharging Screening and Summarization

This is the lowest-hanging fruit. Instead of having a team spend months manually screening thousands of abstracts, large language models (LLMs) can do the first pass. These tools can rapidly screen abstracts and full texts for relevance, identifying key studies with high sensitivity. This is especially powerful in pharmacovigilance, where ongoing literature monitoring for adverse events is mandatory.

2. Improving Pharmacovigilance and Safety Surveillance

Beyond initial screening, AI can detect safety signals from a sea of global literature, electronic health records (EHRs), and post-market reports. This real-time analysis helps identify adverse events much faster than traditional methods, allowing for proactive regulatory decisions and better patient protection.

3. Optimizing Clinical Trial and Protocol Design

Why design a trial in a vacuum? AI can analyze vast datasets from existing literature to help optimize trial protocols, fine-tune patient recruitment, and sharpen eligibility criteria.

The table below summarizes key areas where AI can enhance pharmaceutical research and regulation, highlighting its uses, benefits, and challenges.

| Feature | Use Cases | Benefits | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screening & Summarization | Abstract filtering with LLMs | 80%+ accuracy, faster processing | Moderate specificity, needs human review |

| Safety Monitoring | Adverse event detection from literature | Early issue identification, patient protection | Data quality issues, bias amplification |

| Protocol Optimization | NLP for trial design | Reduced development costs | Explainability, regulatory validation |

| Data Extraction | Cleaning submissions & reports | Streamlined workflows, timely approvals | Privacy risks, model drift |

The “Why”: Massive Benefits of AI Integration

Adopting AI isn’t just about speed; it’s about fundamentally changing the cost-benefit equation of regulatory compliance and innovation.

- Speed and Efficiency: This is the most obvious win. AI slashes review times dramatically. Internally, even the FDA is using tools like its Elsa chatbot to help staff summarize documents and expedite reviews. To the industry, this means faster approvals without cutting corners on rigor.

- Improved Accuracy and Reproducibility: By automating routine screening and data extraction, AI minimizes the human error and fatigue that inevitably creep into manual reviews. This leads to more consistent, reproducible, and defensible evaluations—crucial for demonstrating that “reasonable assurance” of safety.

- Enhanced Safety and Innovation: When AI spots safety signals early, patients are protected. This same acceleration fosters innovation. According to McKinsey estimates, AI could unlock $60–$110 billion in annual value for pharma and MedTech by hastening development and market entry.

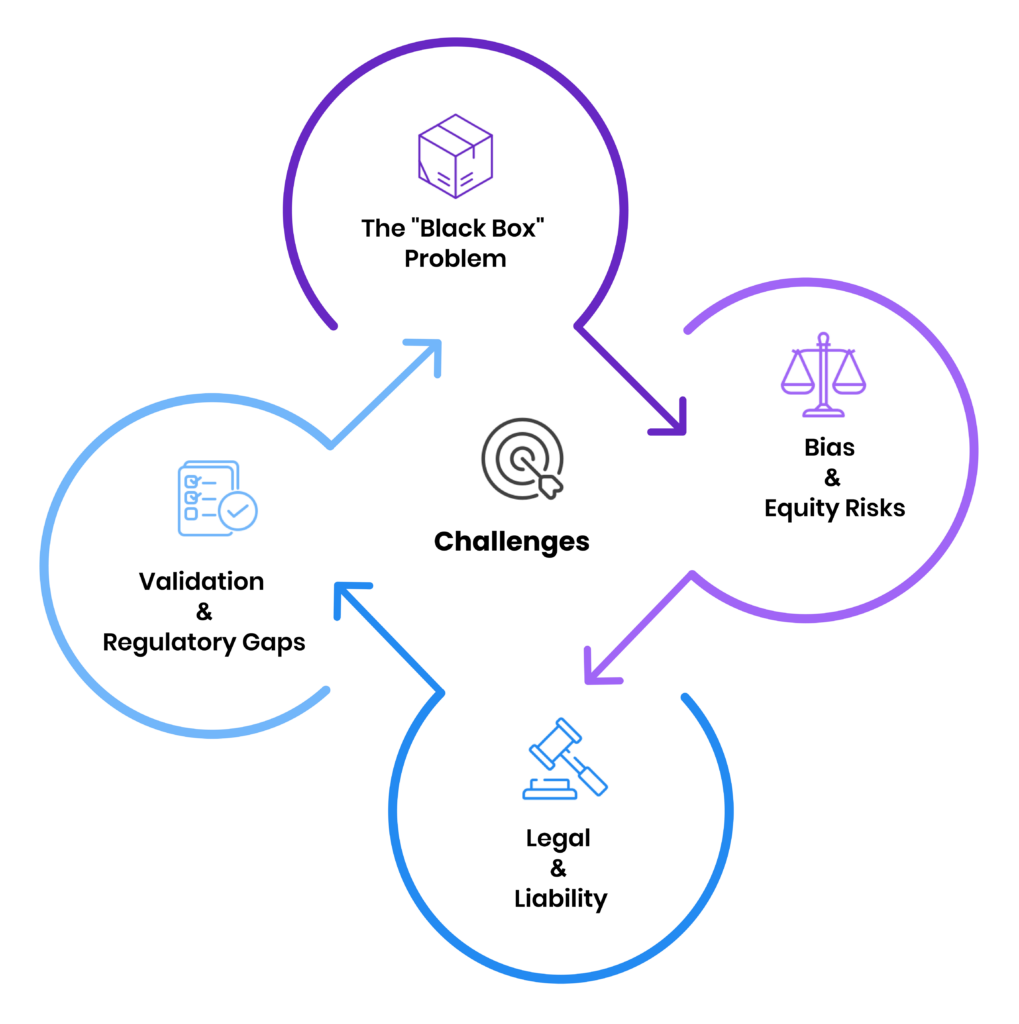

Reality Check: The Challenges

Of course, it’s not all smooth sailing. Integrating AI into a high-stakes, regulated process like an FDA submission comes with thorny issues that demand careful navigation.

1. The “Black Box” Problem

Many advanced AI models are highly opaque. If you can’t explain how the AI decided a study was irrelevant, you can’t defend that decision in an FDA audit. The FDA’s own guidance is increasingly stressing explainability as a cornerstone of trust.

2. Bias and Equity Risks

An AI is only as good as the data it’s trained on. If historical clinical literature underrepresents certain demographics (and it often does), an AI trained on that data can amplify those biases. Recent analyses of FDA-approved AI devices show that demographic data is often omitted, creating a significant risk of biased outcomes.

3. Validation and Regulatory Gaps

How do you validate an AI model? What happens when a model “drifts,” and its performance degrades over time? The FDA is actively developing standards like Good Machine Learning Practices (GMLP), but the technology is often moving faster than the regulations.

4. Legal and Liability

This is the big question: Who is accountable if an AI-influenced literature review misses a critical safety signal? The legal frameworks for AI-driven decisions are still being built, creating liability and IP challenges for innovators.

The Future is Human-in-the-Loop

AI in FDA literature reviews isn’t a silver bullet. It’s a powerful force multiplier.

The TAVR case showed the immense power of leveraging existing literature. AI provides the tools to wield that power at a scale and speed in ways previously unimaginable. The future of regulatory science isn’t about fully automated submissions. It’s about a human-in-the-loop model, where skilled regulatory professionals use AI to handle the volume, allowing them to focus on the high-level critical appraisal, synthesis, and strategic thinking that machines can’t replicate.

If you’re experimenting with AI in your submissions, the best advice is to start small with validated tools and, above all, keep your human experts firmly in control.

What do you think? Have you started implementing AI in your regulatory workflow, or are the challenges still too high? We’d love to hear about your experiences.